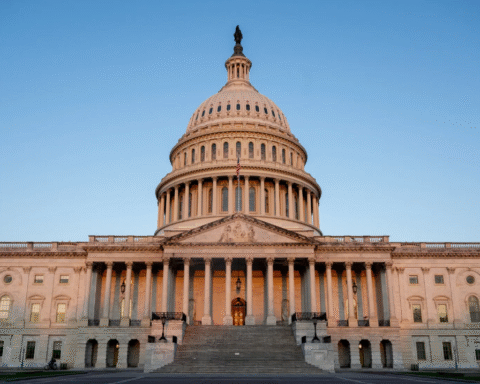

In this analysis we examine the exhibition “MONUMENTS,” co-presented by The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA) and The Brick, which brings together decommissioned Confederate monuments and newly commissioned artworks to probe America’s legacy of public memory. According to Vanity Fair, the show “juxtaposes toppled statues and paintings by living artists” and is being called one of the most talked-about museum exhibitions in the country.

The “MONUMENTS” exhibition does more than display old statues—it lights a signal flare on how the Republic remembers, who it commemorates, and what that commemoration says about justice, identity, and civic equity.

The presence of Confederate monuments—once erected in public places as symbols of dominance and memory—now relocated to gallery walls, stripped of their official pedestal, demands reconsideration. As one of the curators remarked, showing the granite plinth graffitied with “As White Supremacy Crumbles” invites the observer to ask: How have we memorialized power? ABC7 Los Angeles+1

By pairing the physical remnants of monument culture with new works by artists like Kara Walker, the exhibition frames history as ongoing conversation, not static artifact. In her piece titled “Unmanned Drone,” Walker reconfigures the statue of Confederate General Stonewall Jackson into a monstrous hybrid—challenging the mythologized past and demanding viewers see not celebration, but consequence. The Guardian+1

The implications extend beyond art into civic terrain. For communities historically marginalized by Confederate symbolism, the display functions both as catharsis and accountability. The commentary is clear: if the Republic claims that “all are created equal,” then the symbols of its public spaces must reflect, not contradict, that promise. When monuments to treason and white supremacy are relocated from parks to galleries, the message becomes: memory matters, and so does what we do with it.

Yet the exhibition also raises questions about access and transformation: Who participates in the reinterpretation of historic symbols? Who decides how memory is reshaped? If these objects now reside in an art world context, does that ensure broad civic engagement—or does it commodify trauma for a gallery-going audience? The exhibit challenges the viewer’s civic identity: to witness the shift of power—not just physically relocating statues, but conceptually shifting how we remember.

While the lawmakers and the public debate removal or preservation of monuments, the art world has quietly taken a third path: salvage, display, reinterpret. Museums and galleries become civic spaces of reckoning. The Republic’s commitment to unity and truth is tested not only in legislation, but in what we choose to elevate—or dismantle—in our shared cultural terrain.

Closing Insight

“MONUMENTS” is more than an art exhibition—it is a civic mirror. It forces America to look at the monuments it built, the history it told, and the future it imagines. If public art once served power, then what happens when public art calls power into question? The answer matters for the Republic’s story as much as any law or policy.